On the verge of elections, Peruvians have been confronted with a harsh voting decision. As clearly depicted in the New York Times headline: “In Peru’s presidential election, the most popular choice is no one”. However, in a newly polarised scenario, intolerance has come to play, where those who hold different opinions are belittled in the eye of the beholder. With two controversial candidates running for Presidency, communication efforts have mostly been an impediment of rational debate, where a political climate of rejection, uncertainty and social division has mainly prevailed.

In the country with the world’s worst death rate for COVID-19 per capita, expected election results will hardly cast the views of a majority.

Among Latin American countries, Peru is facing an uncertain scenario, where only 32% of citizens in fact voted for the two final candidates in their general elections (Keiko Fujimori (13.4%) and Pedro Castillo (18.9%)). In the country with the world’s worst death rate for COVID-19 per capita, expected election results will hardly cast the views of a majority. Despite this lack of representivity, Peruvian natives including myself were forced to make amends with the political current situation, and reach a new voting decision by June 6th, amongst two candidates who have raised legitimate concerns.

Following the general elections on April 11th, it took little time for political campaigns to begin. On one hand, Pedro Castillo running with Peru Libre awakened the interest of mostly rural audiences with a simple yet powerful message: “No more poor people in a rich country”. However, his efforts remain questioned by a negative campaign from the opposition, describing him as a “communist” and labelling him as a sympathiser of the historical terrorist group Shining Path, accusations he has denied. Some legitimate concerns surround his (1) lack of political experience, (2) his controversial membership in a party with controversial members, (3) a right-wing opposition majority in Congress, and (4) policy proposals in their agenda (either unfeasible, poorly communicated or rather missing).

Keiko Fujimori’s campaign refers to Venezuela’s plunge in minimum wage from 300 to 2 dollars, implying that Peru is leaning towards the same fate with her political opponent: “Imagine having to survive with a minimum wage of s/ 7.50 [2 dollars] a month. #CastilloAgainstYourPocket”.

On the other side, Keiko Fujimori’s right-wing campaign managed to associate her candidacy with the terms ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, where party members and famous Peruvian figures consistently promoted her vote as a ‘lesser evil’ saving the country from the negative economic consequences of a ‘communist’ regime. Despite mentioning a ‘change forward’ and reconciliation in their speech, a common divisive discourse has been promoted – arguably questionable but presumably with success–, where those voting for Fujimori’s opposition would be ‘punishing’ the country with a vote to the left out of ‘resentment’. Nevertheless, Fuerza Popular’s negative campaigning has received some skepticism. Some legitimate concerns surround her (1) policies (including state-delivered bonus), (2) her party’s political behaviour (as seen after her loss in the 2016 elections with a majority in Congress), (3) corruption charges with a sentence of over 30 years, and (4) her father’s legacy, Alberto Fujimori – a Presidential figure with a dictatorial regime from the 90s –, who she intends to concede a humanitarian pardon despite a 25-year sentence for corruption and human rights crimes.

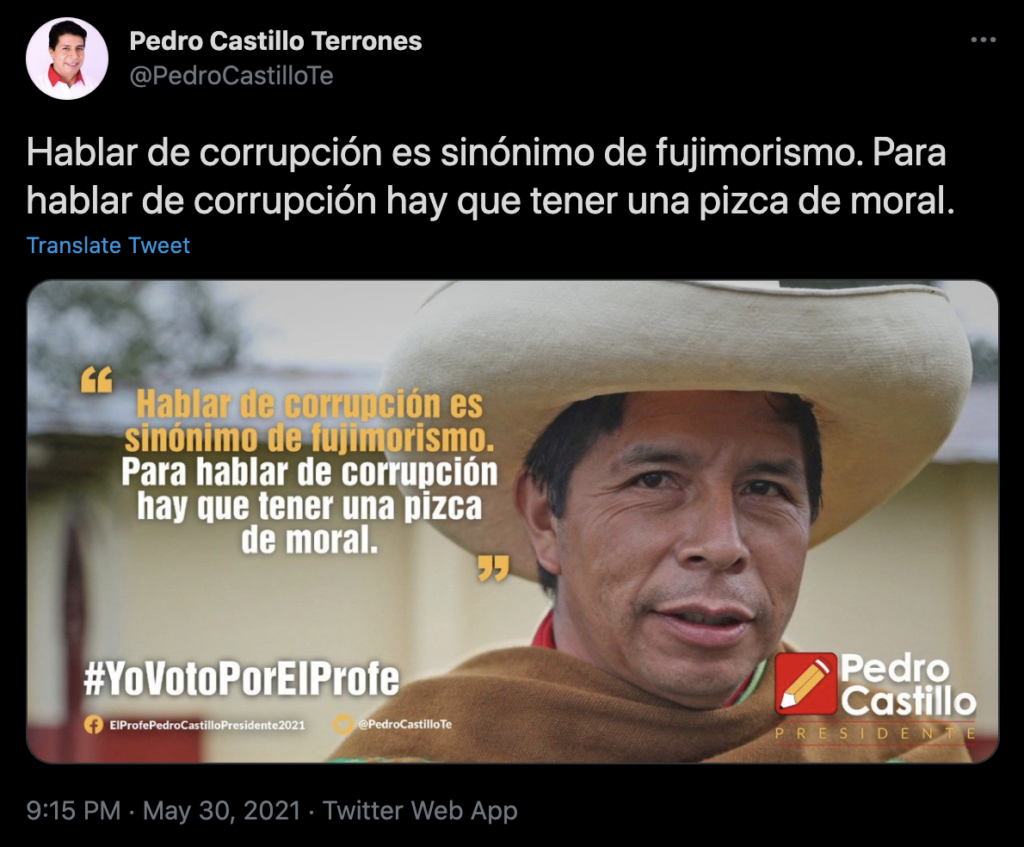

Pedro Castillo alludes to the corruption scandals traced back to the Fujimori family, and some supporters of the ‘Fujimorismo’ movement: “Talking about corruption is a synonym of the ‘Fujimorismo’. To talk about corruption, one needs to have a pinch of morality”

What is curious, however, is how the biggest negative campaign has not come from the party’s official media, but presumably the same voters who joined both candidates, even without being represented.

In the Peruvian media landscape, major national news media also displayed a lack of media plurality and impartiality, with public opinion perceiving they favoured Fujimori’s candidacy. What is curious, however, is how the biggest negative campaign has not come from the party’s official media, but presumably the same voters who joined both candidates, even without being represented. Needless to say, hate-speech between some voters remains relentless on both sides, from times attacking their candidate’s opposition, while dehumanising each one another. Against all odds, Castillo has preserved a majority of votes in polls almost consistently throughout the new campaign. A large segment of Peruvians continue to be discredited in social media for supporting a radical and improvised left-wing candidate, hardly understanding that Castillo’s vote involves those neglected by the state, unconformed with Fujimori’s legacy, or impacted by social inequality, economic hardship and a precarious health system.

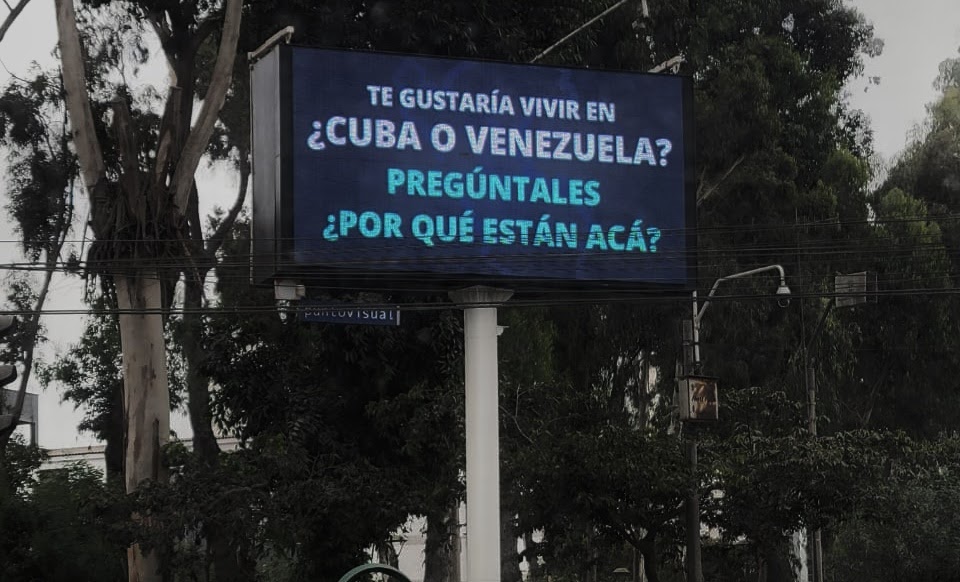

“Would you like to live in Cuba or Venezuela? Ask them why they are living here now”. Advertising panels financed by businessmen against Pedro Castillo’s candidacy have been put around the capital Lima, comparing the situation of countries run by left-wing states and suggesting Peru will suffer the same fate. Photo by: Andrea Valdivia

As a communicator in formation, my country’s complex situation is of great concern. It is hard to summarise in an article the continuous political events, social movements and disinformation that have been remarkably launched in a period of less than three months. With election results coming up soon, I would like to invite my readership to join me in a small reflection, to assess most communication efforts and revisit what it entails to take part in a democracy. For this, I would like this time to address my fellow Peruvian members.

Reflection

Dear Peru,

As a Peruvian, I will not tell you who to vote for, because I don’t think my vote will be better than yours, or yours from mine. I do not tell you this with big advertising panels, or negative campaigns that always seek to misinform, or spread half-truths for the interests of particular groups with their communication efforts. I choose to respect your values, thoughts and interests, to assert your voice at the polls, because I trust that you will do so in a conscious and informed way, and with reasons to help. After all, this is the true democracy that we proclaim, and that above all we must protect.

I advocate for ideas and values, not particular politicians. Regardless of the preferences that some of us may have, and I include my own, we know that one of these two candidates will lead our country, and that they will need our help to carry out this controversial task. Of course, whatever outcome comes out, we must protect this country’s institutionality at all costs. Here lies the importance of a vigilant citizenship, and accordingly, the use of any communication tools that allow the regular citizen to adopt the role of a watchdog. To denounce, to fact-check, to productively debate, but more importantly, to reject violence.

This time, I will vote without representation, but with responsibility. With memory, the information I have, and not under the palliative of a ‘lesser evil’, because as the saying goes: “Evil is Evil. Lesser, greater, middling… Makes no difference. The degree is arbitrary. The definition is blurred”. Everyone decides which one they want to deal with. I thus vote for a democracy without obstructionism, where the vote is free and individual, not led by any fear-driven campaign that allegedly advocates for freedom and democracy. But above all, I vote with freedom of thought, asserting what could be the only one of all the freedoms that will always prevail.

Cover: Andrea Valdivia

Edited by: Sofia Neumayer Toimil