50 years ago, nobody would have imagined the power and the importance that the Internet will have on our societal realms. No one would have thought about the ethical dilemmas that often arise on the Internet. One of the scientists that contributed to the invention of the Internet, Leonard Kleinrock, explained that the creation was only characterized by such terms as “ethic, trusted, free and shared“. But to what extent are we free on the Internet? Can an authoritarian online environment form even in democratic societies?

Tech companies and excessive amounts of power

The non-stopping growth of influence exercised by tech companies has always received criticism and a flood of regulations imposed by governments. Yet, seemingly, it is not enough to alter the ultimate desire for profit. While the issues with data security have been widely discussed, there’s another prevalent legal advantage that we saw all the tech giants use, when Donald Trump was banned from all platforms.

Many Trump supporters and his team claimed that this ban has illustrated censorship and that the rights listed in the USA’s 1st amendment have been infringed. In the first part of this series, we have explained both: the 1st amendment and the user regulations that companies hold.

One thing to bear in mind is that people often make the mistake of inferring that the amendment also protects their rights from corporations. In fact, a law professor, Clay Calvert, has noted that there is no constitutional right to post on social media platforms. Just as newspapers can choose the content they present, private companies have the same right. This means that the 1st amendment itself allows private companies to make decisions and moderate the platforms, unregulated by any legislator. The same is true for European law.

Illusion of freedom

There is already a legal upper hand that the tech giants have. What else is there?

With the growth of polarization in all corners of the world- North America, Europe and South Asia to name a few, and the consequential decrease in the Global Democracy Index, the form of government is threatened. In 2020, the global score was 5.44 out of 10, the lowest it has been since the index was invented in 2006. While the idea of democracy thrives on freedom and equal opportunities, many have been blinded by the extent of freedom offered on the Internet. These are three ways that the illusion of freedom is constructed on the Internet in democratic societies.

Economic dependence

The private sector will not stop expanding. The automation of low-skilled jobs will only increase, as robots are implemented in the manufacturing industry, and artificial intelligence is taking upon daily tasks. With the on-going pandemic, we have seen how the knowledge of the digital realm has become a primary skill and a basic requirement, and the demand for it is only growing exponentially. Yet, at the same time, it is imperative to understand that such a process, just like the industrial revolution in the 18-19th centuries, is a natural one.

What makes things worrisome is that many small businesses must rely on the big Tech giant businesses such as Amazon. For example, the owner of a vinyl shop Assai Records in Scotland, Keith Ingram, has said that they could not have survived during the pandemic without Amazon, as he sold his resources on Amazon marketplace. Combine that with the aggressive tactics of these companies, such as Facebook buying 10% of the stake in the top Indian telecom network, Jio, and you get the memo – they would do anything for profit.

Besides, not only the aforementioned companies are being influenced by tech giants, but individuals who are trying to build a career. People need to sign-up for online employment services such as LinkedIn, a Microsoft-owned social network for professionals, build their image and make themselves attractive for future employers. Many jobs themselves are created by technological advances and the production chain is increasingly reliant on technology. From simple transactions to the way people store their money, for example in blockchains, everything is, now, irreversibly reliant on the tech industry.

Without those tools we are nothing.

It may seem that such tools Big Tech offers are great, that they only expand opportunities and do not harm our freedom in any way. However, what makes it problematic is that without those tools we are nothing; as most people must rely on them for financial success. This results in diminishing economic freedom, in which the Big Tech giants come out on top.

Power relations and Digital Surveillance

However, it is way harder to restrain people’s physical freedom. For example, surveilling the public might be a hassle in democratic and liberal societies with serious democratic controls and processes like the Netherlands. Despite this, there are often ways for the “big brother” to overrule the mass by subtle dominance rather than hardcore policing. This is the same for the tech companies.

Before digging deeper into the core of power relations, we should first understand what “power” really means. To make things simple, Philip Brey’s definition of power where he made intricate yet intelligible elaborations on power with a bi-dimensional property will be used for the following. Firstly, power means both “power to” and “power over”, which the latter is usually the key to power relations.

Take a kindergarten kid as an example, who has the power to punch his garrulous classmate; that is the “power to”. Nonetheless, in reality, the punching kid does not really have the legal power over the classmate unless he has a physically deterring power over his classmate. Both “power to” and “power over” have later been refined as the terms “outcome power” and “control power” in Brey’s paper. Now that we understand the basics of power, power relations should be the following concept we discuss.

Using Dr. Andrew Basden’s terms, power relationships are “relationships in which one person has social-formative power over another and is able to get the other person to do what they wish”. Power relations, hence, is a recognition of the subordination of a particular social stratum to the overseeing institutions and individuals with higher socio-cultural status. With their enormously growing capability in shaping our societies, from social media to FinTech, we can hardly escape from their panopticons, a theoretical paradigm of surveillance coined by philosopher Jeremy Bentham that came into prominence with the introduction in “Discipline and Punish” by the French thinker Michel Foucault.

Both outcome power and control power are obvious here. When technology-supported platforms have become our major channels of communication, tech companies effectively possess the control power to know what we talk about and what our secrets are. Control power will be seen when tech companies have enough data about your consumption patterns, you can be subtly controlled to consume.

More crucially, the importance lies within how the powerful manipulate technologies to exercise their power over the powerless but not what kinds of power relations are strengthened through modern technologies.

For instance, coercion power relations indicate a relationship in which the powerful coerces the powerless by imposing a threat of deprivation. As technology allows for a new form of coercion that does not require physical oppression, coercive power relations have thus become an important kind of surveillance that can be sugar-coated as a positive invention.

China’s social credit system is a case in point regarding non-physical coercive power. It is so far-reaching that it can decide what jobs you can apply for and which shopping malls you can visit by assigning points to you based on the conducts in your daily lives. The Chinese government has 360° control over citizens’ daily lives, including but not limited to the total of 200 million CCTVs installed, and from mobile applications like WeChat to Alipay. The part of coercive deprivation is at play once you get to a point lower than a certain threshold where you simply lose access to everything.

Quite a few years ago, thanks to Edward Snowden, people realized that it was too late to escape from the mass monitoring operated by the National Security Agency (NSA). But at that point, we were only just at the entrance of the dystopia – the disease of digital surveillance has already spread from governments to commercial entities. Despite the formidable ability of big tech firms in exerting their power over netizens, tech companies in totalitarian regimes tend to be, in Hannah Arendt’s interpretation, a banality of evil rather than absolute sovereignty. In other words, tech companies merely act as an extension of the sovereignty instead of the sovereignty itself.

On the other hand, in democratic societies, businesses and governments are more detached than those in authoritarian states. Innovation and technologies that are developed by tech companies, facial recognition technology, for example, might be used for power exercises by the government without involving the companies.

The illusion of freedom will continue to be built.

Nonetheless, tech companies as well consciously nurture loyal consumers in order to retain the dependence on technology. We are fed with the desire and need to use technologies, which is completely interchangeable with the term “consumer attitude” coined by the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Baumann and Tim May in their book “Thinking Sociologically”. Until we reach the tipping point, there is no way back and the illusion of freedom will continue to be built.

Technological exclusion and knowledge gap

Technology, just as newspapers 50 years ago, has continued the same trend and excluded the “uneducated” and powerless from a chance to access the benefits of the Internet, limiting their freedom.

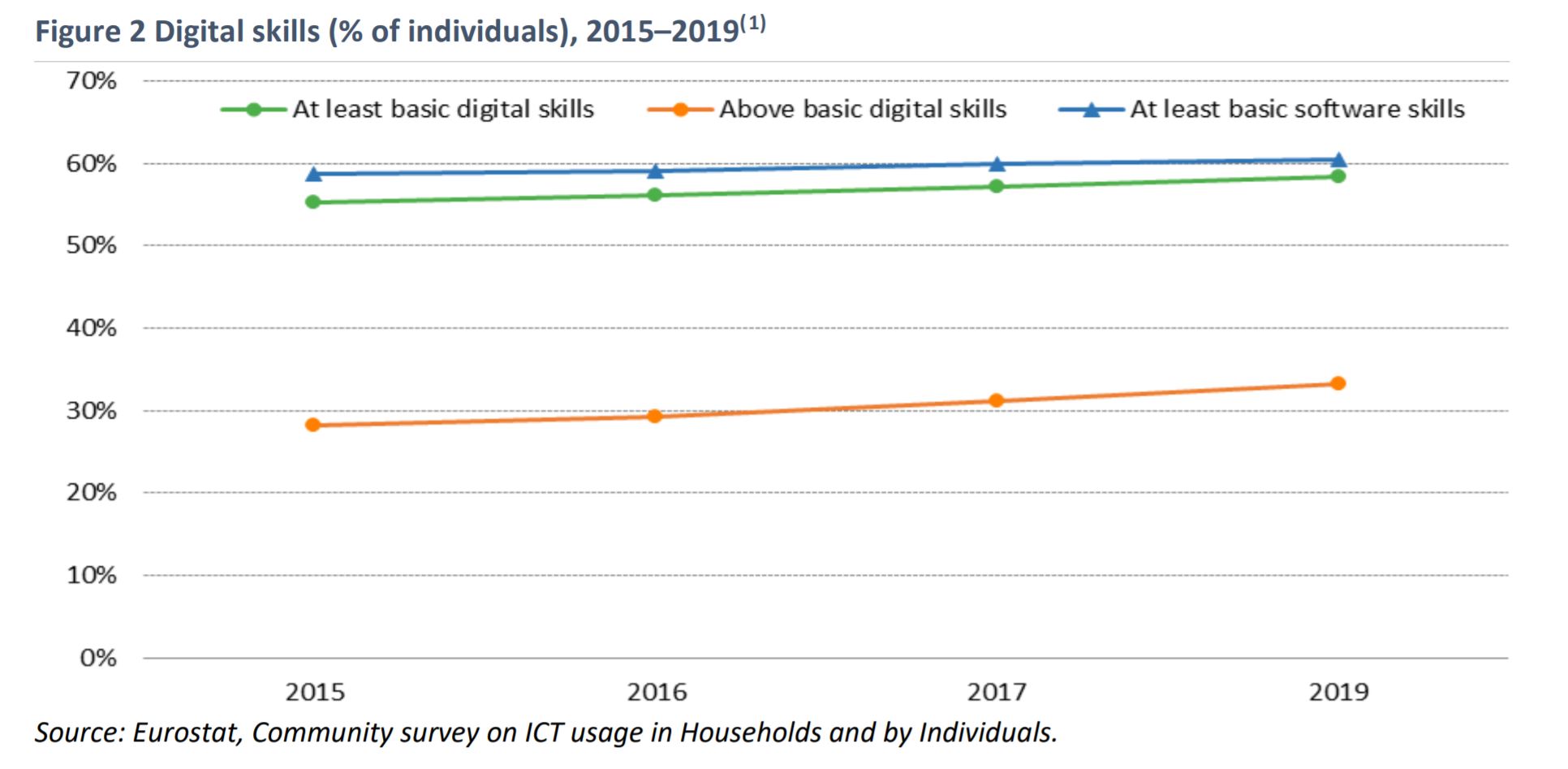

According to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2020, almost half of the EU population do not even have basic ICT knowledge. The lack of adequate ICT skills is the drive of technological social exclusion in our societies. Imagine operating a Strowger or a Frankfurt Bauhaus to call your friend amidst the pandemic: your friend may be just across the street, but you feel as if you’re so close yet so far because you do not know how to dial that vintage thingy. This is exactly how the 42% of the EU population feel when they use slightly “advanced” technology just to complete some daily errands.

While digital transformation (DX) is causing a huge fuss when it comes to the business world, it is becoming more crucial in times of the pandemic with evolving technological capabilities altering the ecosystem of the supply chain, customer-relations management (CRM) and e-commerce thanks to handy research tools like Google Analytics, Klipfolio and Sisense. With the emergence of DX, not only is the producer-side switching to digital heaven, but customers are also forced to migrate.

Technological exclusion not only highlights the inequality in ICT abilities, Internet connectivity is also one serious concern within the discussion of the Digital Divide. The reasons behind the phenomenon might be caused by various reasons including education, income and race. With such a gap between distinguishing demographic groups, some groups are more susceptible to the global shift to the digital world than others.

As Tichenor, Donohue and Olien proposed in 1970 in their paper “Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge”, individuals with higher socio-economic status tend to obtain more knowledge and at a faster rate than those with lower status. Such a hypothesis also applies to social exclusion caused by societal change in the use of technologies in our daily lives. In spite of the closing device divide in the U.S. (i.e. smartphone ownership) revealed by Pew Research Centre, the gap continues to widen in less economically developed countries like Pakistan and North Africa.

As a result, technologies have now become a dominant player in our society, consequently driving out less socially and economically-able persons out of society even if it did not intend to.

Undoubtedly, technological innovations are expanding our opportunities in ways that can make our lives better. Yet, by having an alarming volume of power and the ability to exercise it at any time, tech companies can create a smokescreen behind the construct that we call social advancement. The cost is uncanny, and we have already seen it in societies where authoritarian leaders have used digital technologies to gain absolute control. Our next article will discuss exactly that.

Cover by: Shanmuga Varadan Asoka and Markus Spiske / Flickr