A week ago, my colleague Pipoppinyo (Jaja) wrote an article on how new technology, particularly social media, enhanced activism in Thailand. Just a few days later, Thailand prime minister Prayut announced the emergency state and curfew of Bangkok. Apparently, the move has triggered more locals to participate in the movement and started one of the most crucial New Social Movements (NSM) in the year of 2020 in Asia. From Internet manipulation, derivative art, to crowd chants and hand signals, we could witness various similarities between the protests happening in Hong Kong and Thailand.

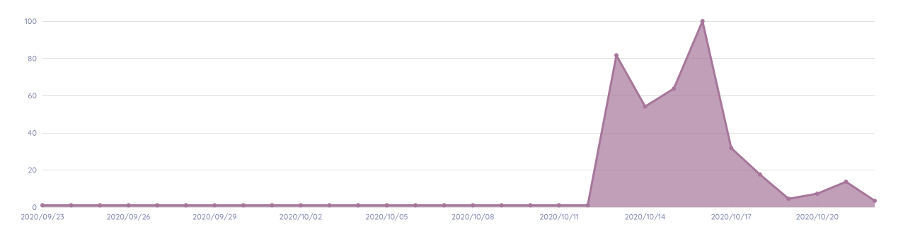

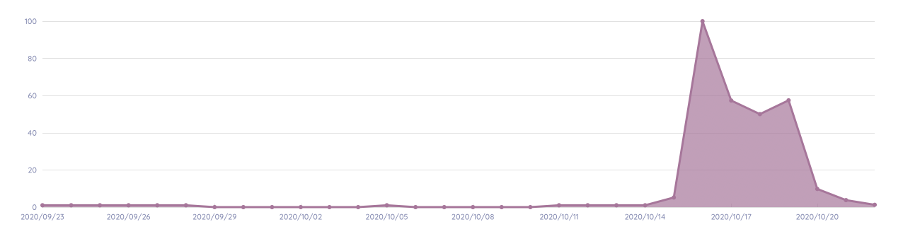

The protest in Thailand has been stirred up for quite a while since the Free Youth Movement declared the three demands and fired up the national protest in July, and it has finally come to a tipping point a week ago when Prayut blatantly neglected the demands of the citizens. I, therefore, wonder how the Thai activists broke out of their wall from Asia and ultimately reached International attention like Hong Kong did last year. This is not a false perception led by the filter bubbles on my own social media accounts, but rather profound truth. According to Google Trend, the worldwide search interest of “Thailand protest” has soared from a maximum of 17 out of 100 back in August, to 100 out of 100 in these two weeks.

However, the resemblance between the protests in Hong Kong and Thailand appears to be rather captivating, this could be due to the lingua franca of protests around the world. No matter where these social movements happen in the globe, similar communication patterns emerge. As of today, it is not uncommon to see comparison photos on social media, depicting a clear picture of how the struggles of two countries are connected through activism and the common language to fight for democracy and their ideals.

Power of the Internet – Hashtags and “For Dummies” on Social Media

Thailand and Hong Kong are not exclusive examples of how activists mobilize and ümraniye escort inflame the crowds to take part in social movements. Tracing back to the Arab Spring, Wael Ghonim once praised how social media (or the Internet in general) boosted activism back in Egypt and he assured that social media was the only thing needed to overthrow the government. The public, especially teenagers as the digital natives of the era, has made rather good use of the platforms to promote and propagate their ideas through creating hashtags on Twitter and “For Dummies”, a kind of simplified and compressed explanation of an issue, on Instagram.

These hashtags have become more than a strategy – a “common language” that you will see in most online social movements.

Social media activists intend to utilize hashtags to spread the message outside of Thailand by creating certain popular strings of words like #WhatsHappeninginThailand, #StandwithThailand, #Milkteaalliance. The former originated from Thailand and the other two are mostly tagged by users in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Interestingly, the trends of the interest indexes of the two hashtags are almost simultaneous, with a 2-day time lag between the hashtags #WhatsHappeningInThailand and #StandWithThailand. This could be regarded as an echo on social media when people in other places give feedback to the origin of the hashtag, and this is how hashtags work in the sense of online activism. These hashtags have become more than a strategy – a “common language” that you will see in most online social movements.

Collective Identity – Chants, Anthems and the People’s Demands

Contrary to the old-school Karl Marx’s concept of class politics, renowned American political scientist Francis Fukuyama has pointed out another form of politics – identity politics in his latest book Identity. It is of utmost importance to mention that Fukuyama’s ideas on identity politics were built on the basis of politics of resentment, which also meant that an identity was developed through shared resentments towards a particular issue or the powered class. Anyhow, collective identity, no matter resentful or not, would be strengthened when there are certain matters available as the representation of an inner-group. Chants, anthems and slogans are cases in point.

The release of “Glory to Hong Kong” is one of the most iconic elements in constructing the identity of the 4th wave localism of the Hong Kong locals, some even regard the tune as the national anthem (political incorrectness alert) of Hong Kong. Thai and Hongkongers have the 3-finger and 5-finger yenibosna escort salute for the expression of the three demands and the five demands they have been asking for respectively. Apparently, crowd chants and slogans are the most extensively used language in the world of activism and protest, perhaps there are no protests without the manipulation of slogans.

The presence of the flags of Tibet, Hong Kong and more in Thailand, is more than just pure substance – they represent an identity.

Other than hand signals and chants, we could also see flags waving in the air amid the protests. The presence of the flags of Tibet, Hong Kong (B&W version) and more in Thailand, is more than just pure substance – they represent an identity. To make a saddening side note, it is also how ultranationalism is developed through brainwashing using symbols and semiotics.

Entertainment of the Rebellion – Derivative Art and Humour

In my last article, I mentioned the significance of humour in times of crises. We can also find examples of humour when we look at how the Thai and Hongkongers deal with their corresponding government.

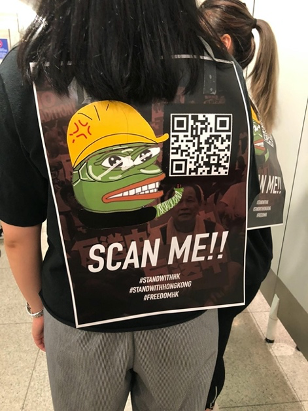

Protestors in both places have manipulated fragments of local cultures to create alluding derivative arts to criticize the culprits of the social unrest. Like every other social movement, people in Thailand love to create anime-related memes and worship them as the symbols of the social movement. Hamtaro is widely used to jeer nişantaşı escort at the money-reaping tax systems and corrupt government, as Hamtaro is a starving anime hamster who loves to eat a lot of sunflower seeds. This symbolism is a representation of how the government is eating up all the resources and starving their people. On the other hand, Pepe the Frog and LIHKG pig are the most manipulated figures in the protests found in Hong Kong.

The effectiveness of the common language seen in protests depends on the contextual differences in distinct countries, some symbols would work better in Thailand, some would work better in Hong Kong. Notwithstanding the variance of cultures, language will always be used as a tool to express the general morale of citizens and their feelings towards those in power. How these feelings are perceived by others and what actions are taken from them ultimately decides the success of protest movements and their communication landscape.

Cover: AP Photo/Sakchai Lalit