What happens once misinformation is corrected? Is it effective at all? A major problem for social media platforms resides in the difficulty to reduce the spread of misinformation. In response, measures such as the labeling of false content and related articles have been created to correct users’ perceptions and accuracy assessment. Although this may seem a clever initiative coming from social media platforms, helping users to understand which information can be trusted, restrictive measures also raise pivotal questions. What happens to those posts which are false, but do not display any tag flagging their untruthfulness? Will we be able to discern them?

When labels elaborated by fact-checkers are strictly applied to certain posts and not to others, users tend to assume that those unlabeled contents are indeed accurate. What Gordon Pennycook and colleagues have denoted as the implied truth effect, is just an example of how corrective interventions may have backfire effects on people’s perceptions, regardless of news’ veracity. Labeling misinformation is a rather delicate task that is currently performed by third-parties, who collaborate with social media platforms, following their guidelines. Nonetheless, the problem does not lie in using methods such as labeling, which is a controversial yet necessary way to combat misinformation. Instead, what should be concerning is how, by applying these countering measures, unwanted consequences may arise. For instance, when false headlines that do not get the chance to be labeled are assumed to be approved, and therefore wrongly perceived as accurate.

Correction of information is not always effective

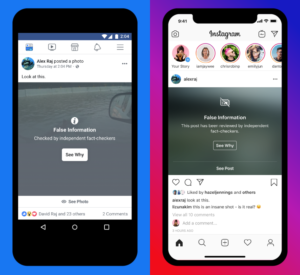

Defining misinformation is a task that academics and even social media platforms themselves have found hard to fulfill. Due to the broad scope of content that misinformation encompasses (both in nature and amount), public pressure has urged networking platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to find feasible solutions for its rapid diffusion. To cope with the convoluted media environment, new measures and updated policies are continuously tested in the hope of filtering content. An example is Facebook’s guideline, which has been developed together with a list of rating options for their fact-checker partners, to review and tag content with labels ranging from ‘false’, to ‘altered’, to ‘missing context’. These are interned to flag any piece of information that lacks a factual background, has been manipulated, or could potentially mislead any audience if no context was provided.

Academic research has found nuanced evidence about the effectiveness of fake news’ correction. Just as unlabeled false posts may appear true to some, correcting misinformation through labeling may not be effective after all, as false information may have a prolonged effect on those who become exposed to them. As Stephan Lewandowsky and colleagues claim, people are more likely to remember the news content of a post, rather than the corrective label attached to it. Thus, the influence and spread of fake news may persist, regardless of attempted countermeasures to combat it. This to say that despite the prominent action that has been embraced by social media platforms, measures may be insufficient to reduce the traffic of misinformation on personalized NewsFeeds.

Thus, the implementation of correcting measures may not only affect our awareness about fake news, but also our attitude toward true ones.

Given the massive amount of user-generated information that is published on an hourly basis, not only false information is disseminated, but so is true content. Thus, the implementation of correcting measures may not only affect our awareness about fake news, but also our attitude toward true ones. Indeed, not only users may become more inclined to question content displaying false information, but attaching labels may also lead us to be more skeptical about media content overall.

As spillover effects and generalized distrust come into play, misinformation raises new potential challenges for those news producers, consumers, and stakeholders involved in the news productive chain. By threatening the legitimacy of news sources, the role of social media platforms as gatekeepers is even more essential, as they are responsible for algorithmically filtering and removing news available on online platforms, but most importantly, for enhancing democratic processes at a societal level.

Corrective strategies, are labels a lost cause?

Labels are definitely not a lost cause. Arguably, the mere act of labeling unreliable content already represents an opportunity for users to reflect on the accuracy of information, and when possible, they help to spark skeptical elaboration and critical thinking about NewsFeeds’ content. Most social media platforms have developed fast responses against the spread of misinformation concerning urgent issues such as COVID-19 and the 2020 US elections. As for COVID-19 news alone, Facebook claims to have removed “more than 12 million pieces of content about COVID-19 and vaccines”. In the case of Twitter, the platform regularly monitors content related to COVID-19 to ensure that false Tweets don’t gain visibility, using warnings and labels to discourage their spread.

As seen, strategies involving the use of AI systems have actively been implemented by social media platforms, including the flagging of misinformation and the detection of unauthorized copies of false COVID-19-related material. However, as networking platforms have acknowledged themselves, the correction and limitation of misinformation are not enough to counter the latter’s effects. As platforms become aware of these negative potential outcomes, some have been keener to provide complementary options, such as Facebook’s ‘COVID-19 Information Center’ providing Instagram and Facebook users direct access to reliable information from experts and official sources.

With social media platforms failing to counter the dissemination of misinformation, our online media environment becomes even more complex, serving as a platform where content lacking veracity continues to spread and widely permeate in our information system. Now, it is important to understand that due to people’s biases, predispositions, and opinions, labels may often result as inefficient, or rather easily forgotten. More importantly, it is inherently challenging to even come up with a close estimate of how much fake news is currently in the system. No to mention the content we might not be aware of and still process daily. As new alternatives are being developed, including deep fake detection and media provenance solutions to authenticate content, guidance for users is urgently needed. In the meantime, the latter must be continuously warned about unreliable information by existing methods such as labeling indeed.

Cover image: PhotoMIX-Company on Pixabay

Edited by: Cecilia Begal